Frontlist | Are women free to loiter on the streets of India in 2021?

Frontlist | Are women free to loiter on the streets of India in 2021?on Jan 29, 2021

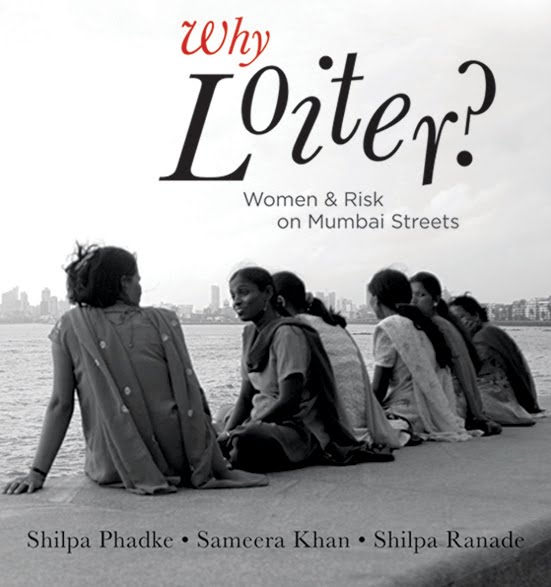

On the 10th anniversary of their book ‘Why Loiter?’ Sameera Khan, Shilpa Phadke and Shilpa Ranade talk about women’s access to public places

Ten years ago, when writers Sameera Khan, Shilpa Phadke and Shilpa Ranade wrote Why Loiter?: Women & Risk On Mumbai Streets, India was yet to experience one of its most horrific crimes against a woman in public—the 2012 gang rape and murder of a student in Delhi. Since then, women have occupied the streets in numbers to raise their voices against harassment and violence, defy the limits imposed on their freedom of movement, and rebel against the fences put up by patriarchy.

Movements like Pinjra Tod have gathered momentum, the women of Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh set a template for public protests all over the country in 2019, and recently, women have joined the agitation against the new agricultural laws. Why Loiter? was centred on women on the streets of Mumbai but it raised issues of urban planning, women’s right to take risks, and sought to bring about attitudinal changes, issues that continue to be relevant. Lounge speaks to the authors to understand their views on women’s right to loiter on the streets of contemporary India, as equals of their male counterparts. Edited excerpts:

Ten years ago, ‘Why Loiter?’ started a spirited conversation about women’s right to freely access public spaces. How would you describe the current state of that conversation?

In our book, we make a case for loitering as a fundamental act of claiming public space and ultimately, a more inclusive citizenship. We believe the right to loiter for all has the potential to undermine public space hierarchies.

When we first talked about women’s right to pleasure in the city, we were met with resistance even in feminist circles. It was considered a frivolous demand considering that women still have to fight for their basic rights. Today, this idea and the term “loitering” as applied to women’s right to public space has become part of not just the feminist lexicon but part of everyday language among young people across the country. In this sense, we have seen an unequivocal shift in the conversation of what constitutes women’s fundamental rights to the city. We have seen some amazing young women take our conversation further by initiating their own movements questioning early curfew at women’s hostels, expanding women’s access to the night, sitting at dhabas to drink chai, and so on.

In the book, you argued eloquently about women’s right to take risks. A year after it was published, in 2012, India witnessed one of the most heinous attacks on a woman in a public place in recent memory. How do you evaluate the impact of the Nirbhaya case on the ‘Why Loiter?’ movement?

The Delhi rape case was a major turning point in the conversation on women’s access to the city. The idea of unconditional freedom—that women had the right to be out in the city unmolested—irrespective of who they were, who they were with, what time it was, or what they were wearing was made visible in public demonstrations for the first time in the country.

On the other hand, a singular focus on the spectre of violence that looms over women in public space in the reportage of such cases has done little to further women’s rights to public space. This focus on women’s vulnerability in public space contradicts two well-documented facts: one, that more women face violence in private spaces than in public spaces, and two, that more men than women are attacked in public. In effect, it ends up curtailing women’s freedom by providing unprecedented justification to the physical and moral policing of their movements by the family, community and the state.

A key section in your book considers gender bias in urban planning vis-à-vis women’s movement in Indian cities. Do you think policymakers are more cognisant of this problem now?

In Why Loiter? we make a case that designing for an imaginary “neutral” user—inevitably the privileged male—is a key stumbling block in making the city welcoming to all. There is an increased awareness and discussion on women’s relationship to the city today, as is seen from the inclusion of the gender aspect in the Mumbai Development Plan (DP) 2031. However, once again, as the example of the Mumbai DP reveals, the translation of this into action is often limited to projects that can be visible demonstrations of intent, such as hostels for working women, rather than those that can address more systemic issues of exclusion that are inbuilt into the planning of the city, such as gendered access to transportation. In many cases, the nod to gender-sensitive planning and policymaking tends to remain a lip service focused on meeting development goals or good PR.

From Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal allowing free travel for women on the Metro to Madhya Pradesh CM Shivraj Singh Chouhan’s plan to monitor women outdoors, politicians in India, mostly male, come up with regressive, well-meaning or lopsided plans. Do you think this is a function of the skewed representation of women in India’s political life and public policymaking?

The Delhi Metro proposal for free travel cannot be compared in any way to the Madhya Pradesh plan. The Delhi proposal is based on the idea of affirmative action promoting access for women who are otherwise structurally discriminated against in their access to the public. It enables women from resource-poor families to attend college or work further away from home. The Chouhan government’s plan, on the other hand, is based on an outright patriarchal vision of women as essentially belonging at home, to be protected when they access the public.

The Delhi transport proposal enhances women’s access to the public. The surveillance suggested by the Madhya Pradesh CM infantilises women, denying them agency, and has to be seen in connection with the “love-jihad” Bill against inter-faith marriages controlling whom women can choose to marry.

It’s 2021 and the Supreme Court is still trying to put women at protests back home. How do we counter the mindset of ordinary people when the highest court of the land doesn’t seem to help?

It is horrifying that in a year that has seen women of all ages physically occupy Indian streets for a long stretch of time in protest against the CAA-NRC-NPR legislation (perceived discriminatory rules on citizenship, and towards citizens) before the pandemic and now against the farm Bills, that the Supreme Court should ask that women not be “kept” in protests. One might read this precisely as a reaction to women, including minority women, exhibiting their agency, the right of their bodies to be in public space in protest and for pleasure. We need to push back very hard against such regressive strictures.

As we have said in our book, what we need then is to redefine our understanding of violence in relation to public space—to see not sexual assault, but the denial of access to public space as the worst possible outcome for women.

Do you think the pandemic and the consequent lockdown has stalled the progress of the ‘Why Loiter?’ movement?

It can become difficult to imagine women claiming the right to loiter when public spaces—which are in any case shrinking as the state rushes to privatise them—are fraught with “risk” for everyone in the pandemic. However, the pandemic has seen women being affected differently from men. For example, the reality of homes being unsafe violent spaces for women has been outed.

The pandemic has brought into stark relief the class divisions that regulate our access. From the humanitarian crisis of poor migrants leaving cities, to the strictures of purity and pollution applied arbitrarily to domestic workers, to the digital divide, the pandemic has underscored the lines of fracture and exclusion in society. The other offshoot of the pandemic is that the online space of public conversation has become an important site for many of us to engage in the public sphere and shown that loitering on the internet can be as fraught with risk for women as the real space of the city. The pandemic has reinforced our argument that women’s access to the public space is connected to that of other marginal citizens, both on the streets and online.

Authors

Frontlist Book News

Indian authors

Sameera Khan

Shilpa Phadke

Shilpa Ranade

Why Loiter?: Women & Risk On Mumbai Streets

Women Author

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.